Protest Against Hunger

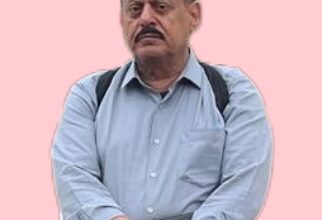

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

I am often provoked by poverty, hunger, injustice, and corruption. I am stirred by oppression in all its forms, even when it wears the guise of a father, teacher, leader, saint, or priest. What angers me even more is the arrogance of power, its obstinacy, and the hollow pride that stands defiantly against truth and the justice I dream of and care about. I have never come to terms with injustice, no matter how long it endures. I do not tolerate it, even though I am inclined to forget, until it is broken, overthrown, or liberated from its grip.

My spirit does not rest or quiet down; it remains ever restless for discontent, rebellion, and revolution. I am perpetually haunted by anxiety and dissatisfaction. Even if I seek solace in silence for a moment, or feel a temporary disillusionment, or turn a blind eye to the truth for a while, or even conspire for personal reasons, I still engage in a fierce internal struggle with my conscience. The rebuke of my conscience kicks at me from within like a wild donkey until I return to what is right, as best as I can.

Perhaps this nonconformist spirit is what led to my exclusion from opportunities that others seized while I consciously, willingly, and with asceticism let them slip away. I have always viewed them, and still do, as mere traps and schemes, a prison of enslavement with no escape.

At times, I feel weary and burdened, but as soon as I rest a little or catch my breath, I find myself returning to the fray, again and again. I return to proclaim my rejection, to act with defiance, and to resist until matters find their proper course or come to an end.

I engage in a patient struggle with reality, much like Sisyphus, the symbol of eternal torment with his rock, or like Satan, who defied the collective and disobeyed his Lord alone and in isolation, fulfilling the divine will inscribed in the preserved tablet, placing it above his own selfishness. I strive to amplify the voice of the oppressed as far as possible, even if some of it is consumed by worms. I constantly seek to align myself with those who suffer in their just causes and resist those who perpetrate this injustice, oppression, and enslavement, regardless of who they may be.

I may appear perpetually anxious and dissatisfied with the course of events and the state of affairs, perhaps even enraged by this bloody world and its system rooted in injustice and exploitation, rebelling against the fates I feel are unfair. I have come to fully understand this today, recalling how it all began during my first protest as a teenager, or in the early days of my youth.

* * *

In the “Proletariat” school, driven by hunger and protesting the lack of improvements in our meals and the power outages, a large number of students, myself included, went on strike.

We refused to attend classes, taking to the streets to protest the poor quality of our food and demanding better provisions. We blocked the road between Lahj and Aden with stones, preventing vehicles from passing—a bold act in that era, highly sensitive in nature. Any such protest was often classified as a counter-revolution, with some politicians interpreting it in the most negative and ugly terms, attributing motives beyond what we could bear. However, the presence of protesting students from Al-Dha’le and Radfan helped shield us from many of those assumptions and mitigated the consequences we might have faced.

Many students participated in the protest, refusing to attend classes. Some faltered after a day or two, while others chose safety, avoiding this rare and unprecedented act of dissent.

My classmate, Ahmed Mussed Al-Shuyaibi, describes what transpired during the first spontaneous student uprising against the deprivation of basic rights like food and shelter. The spark was ignited by power outages due to the education administration’s failure to pay the electricity bill. The students took to the main road, blocking the route between Lahj and Aden.

The students from Al-Dha’le were at the forefront of the protests. I admired those “madmen” who defied the darkness, faced hunger, and challenged its consequences.

I looked upon those who did not protest with disdain and contempt, questioning why they were gripped by fear and weighed down by despair, failing to rise against hunger and its perpetrators.

I respected the students brave enough to protest, striving to carry the voice of hunger to the highest authorities in the country.

The officials in the province, particularly in education, were alarmed by the potential repercussions of these protests on their positions and jobs.

They descended to meet with the students, eager to hear the protesters’ demands and discuss them, after failing to intimidate us or deter us from continuing our protest and returning to our classrooms.

We did not cease our demonstration until the arrival of Ali Antar, who succeeded in calming us with the promise: “You’ll go for a week and return to clean food.” He ordered transport to take the willing protesters and discontented students back to their districts for a brief holiday while matters were resolved and their demands addressed.

Such a protest against the revolutionary authority, especially during that sensitive period, was a bold and courageous act by all measures.

To ignite a protest in a school bearing a noble name in a state that claims to embrace the theory of scientific socialism and strives to establish a “proletariat” state perhaps reveals the fragility of some of that claim.

This protest yielded significant improvements in nutrition, cleanliness, organization, and the restoration of electricity. It marked the first protest in which I participated.

* * *