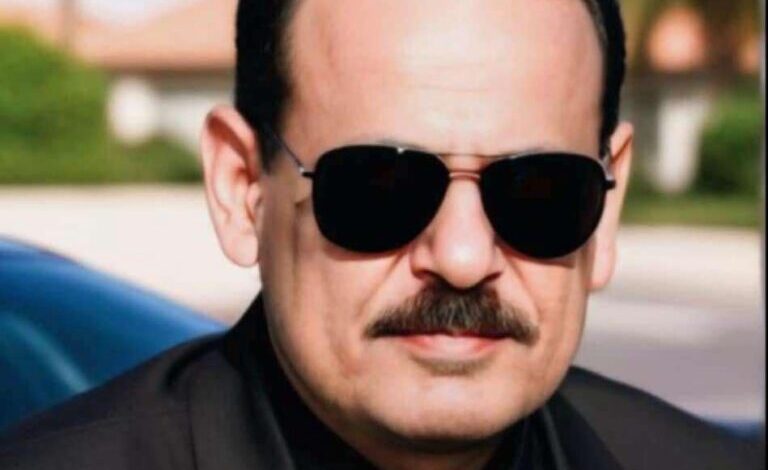

In Prison

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

As I found myself in the grip of the soldiers, one of the injured man’s relatives rushed in-likely his cousin, named Talal. He was tall and well-built, with a complexion leaning towards a tan. The moment he laid eyes on me, he was taken aback by my appearance. I looked nothing like what he had expected; before him stood a diminutive figure, lacking anything that could compare to his injured cousin. He shouted angrily at those present, “We cannot accept even ten of this!”

Perhaps he was right, if we measured it by his standards. Indeed, I appeared small, exhausted, pale, distracted, frowning, and unfortunate, while his injured relative looked robust, with features that exuded affluence, and a foreign demeanor that spoke of comfort and ease. His hair, cheeks, eye color, and a body filled with flesh and fat all contrasted sharply with my own.

I began to observe some of what was happening around me: the preparations for my imprisonment, the soldiers’ insistence that I should not escape or evade capture. They scrutinized my grim, silent face. I noticed puzzled expressions on some of the onlookers. I sensed that there were words they longed to say, but held back for reasons perhaps only they understood.

I watched as the written order for my imprisonment was prepared. The order was handed to the booking officer, and I was taken to the holding room. The lock and chains were undone, and the door to the room was opened. I was instructed to enter, and the door was secured with chains and a large lock. In that moment, I felt as though I had committed a grave and terrible offense.

It was the first time I had been imprisoned-a bitter experience that I was entering for the first time. A profound sense of being bound in freedom surrounded by walls, barriers, and iron enveloped me. The holding room was about five meters long, perhaps a bit less, and two meters wide, with a small window barred with iron. I felt as though I was stepping into a darker phase of my life, and I needed to brace myself for the worst. An ominous unknown awaited me, its details and conclusion unclear.

The holding room was empty, with no other prisoners but me. Perhaps the occasion of visitors required this, or maybe some inmates had been transferred to the facility located on the upper floor, or there might have been another prison in the center building.

I wished that Salmeen and Abdul Fattah would visit the holding room, hoping to see them up close. Perhaps they would check the corridors or even visit the officers and soldiers stationed there, but unfortunately, that did not happen. Instead of the cheerful encounters I longed to witness—hands waving in greeting-I found myself staring at a dismal ceiling and mute walls. My only companions were the scribbles and memories of previous prisoners on those bare walls. I yearned for a magic pen, a piece of charcoal, or even a nail to scratch my memories and the history of my imprisonment onto the wall, to tell future inmates, “We passed through here, and we stayed for a while.”

By a twist of fate and misfortune, my mother was ill and resting in the same hospital that treated the injured man. In fact, the injured man’s brother was the very director of that hospital. I began to feel anxious about my mother. How would she be treated after my actions that had stained her brother’s blood? Would they expel her? Would she suffer harm, or be given poison disguised as medicine, a means of seeking revenge for their injured kin against my mother, who was there for treatment? My worry and apprehension grew, along with distant fears regarding my mother, who had no one else there but me.

More than an hour after the end of the speech ceremony, I was summoned by the criminal investigation officer. They brought me to him, and I saw the knife on the table, carefully secured as evidence of the crime. The officer instructed his clerk to open the report and began reading an introduction that made me feel the weight of the situation-that I was on the path to court and facing penalties beyond my capacity to endure.

After a series of questions and answers, along with an acknowledgment of what was evident, I was confronted with the knife, the instrument of the crime. Once the facts and details I recounted-consistent with what had occurred-were established, the officer ordered my return to the holding room. The investigation lasted about an hour, during which my statements were recorded, while the reality of my crime stood clear and undeniable.

Upon my return to the holding room, a man from the popular forces named Abdulwahab Othman peered in through the door. He had moved from Al-Qabaitah to the southern area of “Al-Ghol” in the past, and his roots traced back to Al-Qabaitah, from where he and his brother Abdulhamid hailed. They were cousins of our friend Fareed Mohammed Othman Al-Qobati.

His presence felt like that of an angel offering me assistance without request-a rain cloud providing relief. It was a mercy from fate that cares for and remembers those it loves, reminiscent of Jacob’s love for his son Joseph or Abraham’s paternal bond with Ishmael, but without a knife, ransom, or sacrifice. Instead, he provided me with a mattress and a blanket, perhaps he had made an effort to procure them.

Abdulwahab worked just a few meters away from the holding room. His smile lightened a burden on my shoulders that I felt too heavy to bear, especially for someone so young. His smile brought me the comfort and peace I desperately needed. His sweet words made me feel as though I had known him for much longer than my brief life.

After an hour, I felt utterly exhausted. Sleep began to weigh down my heavy eyelids, and fatigue dulled my weary eyes. I succumbed to slumber, sinking into a deep sleep. Suddenly, I woke up after several hours! I rose as if possessed, or as if a spirit hovered above my head. Bewilderment washed over me as I asked, “Where am I? Where am I?” After a moment, I gathered the scattered pieces of my consciousness and regained a sense of reality. I realized I was imprisoned, I had committed a crime, and there was a victim, injured, perhaps facing death

After a brief awakening and drifting back to sleep, I began to adapt to my circumstances. I returned to sleep again, only to awaken a few hours later, now more aware of my situation. I felt somewhat ready to adjust, and some of the initial, overwhelming anxiety had faded.

My brother’s companion, Saeed Abdulwali, had traveled from Al-Tur Al-Baha to the village. He informed my brother about what had happened. The next day, my brother came from the village to Tor Al-Bahah center. Fortunately, the stab wound was not deep, and my brother was well-respected by the authorities at the district center, particularly by Mohammed Taher, the station chief, and Ba Ali, the organizational officer. Since I was still considered a minor, these factors led to my release on my brother’s guarantee. However, I was summoned and detained by the investigation officer several times, and on one occasion, I was held alongside the injured man after he had recovered. The case was eventually resolved, and its file was closed.

My mother was unharmed, but she was gripped by fear and distress after learning from some of my classmates what had transpired. The hospital director, the brother of the injured man, was a responsible doctor who cared deeply for his patients and did not seek revenge.

What happened was an act of recklessness, folly, and poor judgment at an age when I was still quite young. I felt a profound sense of alienation, constant provocation, and a sense of superiority from what appeared to be a gang that pushed me to commit an act I later regretted and learned from.

I also regretted not being able to see President Salmeen and Abdul Fattah Ismail. After a period of several months, I was shocked by the news of Salmeen’s ousting, a man beloved and popular among many ordinary people, including the kind-hearted Abdulwahab. In contrast, Abdul Fattah Ismail’s popularity was largely among the elite, and he held significant respect among intellectuals.

The question remained: Why does politics ruin relationships with those we love? Is it the nature of the world and power, or the absence of reason and wisdom? Is it the presence of recklessness and folly, or a lack of experience? Perhaps the reasons had become complicated and intertwined? The cycles of violence witnessed in the south had catastrophic results, toppling one individual after another until they ensnared everyone, burdening society beyond endurance and distorting what should have been beautiful and exemplary.

* * *