A School Without Co-Education

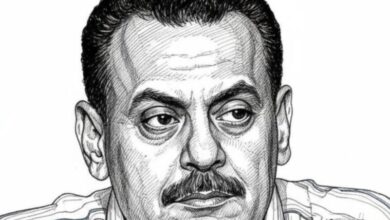

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

The students of “Proletariat School,” numbering in the hundreds, were all male. There was not a single female student in the school—a barren wasteland devoid of green plants or gentle breezes, even in the late hours of the night. No dew, no drops of rain; only a harsh dryness that cracks the earth. “No water, no greenery, no beautiful faces!” There was no joy, no hope, no promise—only desolation and dust in every direction.

The past, burdened with its weight, views segregation and the separation of genders as virtuous behavior dictated by the values of good morals. They elaborate on this, until heads, cloaked in shame and rigid fatwas, rise beneath their aprons. Meanwhile, we see that balance, a thriving life, and protection come from awareness, refined ethics, and proper upbringing.

Mixing offers attraction and competition, transcending our heavy heritage, and overcoming deeply entrenched social constraints. Separation and isolation weigh heavily on us, alienating us from the era we live in and leading us backward, away from the future we desire. Life under the pressures of repressed complexes, swollen with intense tension, and rampant sexual obsession grips our thoughts and distractions, consuming our awareness and attention, resulting in unhealthy outlets and disgraceful behavioral deviations, while abandoning what is considered normal and healthy living.

It is not normal to wait for the weekend to travel over ten kilometers just to catch a glimpse of a girl you love; you may find her, or you may not, leaving everything to chance—of which there is little and rarely any.

It is not normal to harbor a deep love in silence for three consecutive years without knowing where the one you love is! I am not well if I spend three years loving from a distance, unable to confess or reach out to the one I adore!

It is unnatural for shame to consume you to the point where your forehead furrows under its weight, causing you to miss out on opportunities one after another, while your limp love yields nothing but disappointment, sorrow, and loss.

It is not normal to wish to spend a single night with the one you love, only to condemn yourself to death with thirty bullets in an unblessed morning. This is what I longed for on a suffocating day, ablaze with the revolution and volcanoes that churned within me—a struggle against a tyrannical instinct, an insatiable sexual hunger, and a predatory, terrifying urge.

If mixing were allowed, the utmost I could imagine would be the pursuit of love and the happiness we desire—the search for a passionate, complete love, for the dream knight who embodies a life of joy and authenticity, the suitable wife for the future. Yet, in our current state of separation, I find some who travel miles to engage in deviant acts with a female donkey, while others go to “Sisbane” to quench their burning sexual desires in exchange for money.

Some of us watch television, following series and films, then live out the roles we imagine, sharing moments with actresses like Shams Al-Baroudi or Yosra. I found myself in heated debates with friends about the most beautiful women, dividing ourselves into teams, arguing passionately as we extolled their virtues, wagering on who was the most deserving of admiration. We sought out judges to settle our disputes, and when a ruling was unfavorable, we searched for another judge, only to witness the judges themselves divide, seeking yet another ruling: Who is more beautiful, Warda Al-Jazairia or Aziza Jalal? I stood in support of Warda.

Our dream was to learn and find a livelihood that would sustain us against hunger. When this dream, or some portion of it, was realized, we began to see mixing as a dream and a necessity. Human aspirations do not end with the fulfillment of a specific dream; dreams, too, breed like light.

My friend Mohammed Abdulmalik and I would go to Aboud Mixed High School, where he had a relative living within its premises. There, I witnessed freedom pulsating with light, love, and reconciliation with oneself, while I silently endured pain, alienation, and loss.

I felt a profound sorrow as I compared “Proletariat School” to Aboud School, which thrived in mixing and vibrated with life, love, and joy. Our school, in this comparison, seemed as deprived as we were—a barren desert, with winds blowing dust into our weary eyes throughout the year. Meanwhile, Al-Shaheed Aboud High School in Dar Saad appeared more than just an elusive dream—and it pains me even more today to know that they have even changed its name.

I always wished we could stage a protest demanding our right to mixing, akin to the protest for better nutrition, but my shyness held me back from even whispering such desires. Inside me, a volcano roiled and boiled, while my shame and modesty formed layers of steel and ice that suppressed any revelation of my inner turmoil.

I swelled with repression and congestion, striving to shatter every tradition and belief. I attempted to view matters with a perspective that perhaps transcended a thousand years into the future beyond what was prevalent. I yearned for a world of vastness and orbits, a world unburdened by constraints, borders, and traditions. It was a surge from a deep well, the aftermath of sexual urges weighed down by shame and heavy customs encased in isolation and separation, by fire and iron.

I was radical to the point of madness, and such madness would not have existed were it not for my awareness of this oppressive shame, the strict social repression, and the immense pent-up frustration. I bear witness to my friend Muhammad Abdul Malik’s balance in contrast to my thoughts, which swung between the hammer and the anvil, caught between the fire of suppressed desires and the heavy burden of shameful reality.

I studied and graduated from Proletariat High School in 1981 with a score of 82%, a challenging achievement at that time, qualifying me for a scholarship abroad. Yet I remained shy and lacking in knowledge, without anyone to advocate for my right to justice or support my case in any competition.

* * *