Executions

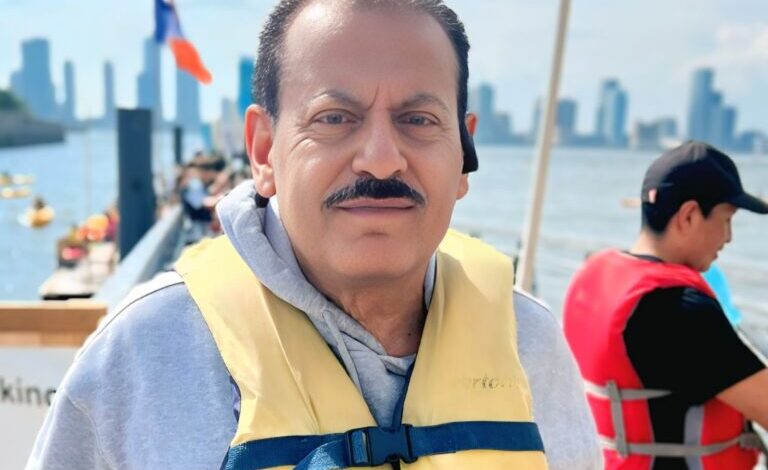

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

As I was engrossed in my studies during my first year at the Faculty of Law, the events of January 13, 1986, unfolded. Here, I will recount the part concerning the Unity Brigade, stationed in Abyan Governorate, about 2-3 kilometers from Zingobar, the capital of the province. Many of its members and officers hailed from what was known as the northern beloved homeland. I assert that my dedication to studying law saved me from certain death—not for any particular reason, but simply because I was from the north. Under the label of “northern,” most officers, non-commissioned officers, and northern soldiers were purged, with only a few managing to escape, while an even smaller number—merely a handful—found themselves surrounded by confusion and questions.

The brigade commander and the head of operations were not fond of me, nor was I of them. I felt an acute sense of alienation the moment I encountered either of them. My spirit would tighten every time I met with one of them or even passed by their side. Occasionally, I was beset by an inexplicable feeling that heightened my discomfort and sense of estrangement. In time, I learned that my instincts were indeed correct.

Politically, I was neither aligned with them nor favored; my closest friendship was with an officer famously known as “The Goblin,” who served as a political deputy for one of the three main battalions in the brigade. He had come from the north during the Abdullah Abdulalem events and was politically affiliated with the Revolutionary Democratic Party, later joining the Popular Unity Party after the merger. Socially, he belonged to one of the marginalized groups and, like me, was not favored by the brigade commander or the head of operations. Tragically, he was executed during the January events.

I was also noted by them as the head of a party cell in the brigade named “The Martyr Abdul Latif Al-Halimi Cell,” affiliated with the Popular Unity Party, known as “Hushi.” Although our party work was primarily political and focused on the north, that alone was enough for them to consider me a suspect of the highest order.

Two weeks after the onset of the events on January 13, I went to the brigade headquarters, only to learn that approximately 85% of my friends and colleagues had been eliminated—officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers. Some were killed in Wadi Hassan, others in prisons, dungeons, and detention centers, while still others were executed within the brigade’s own camp, having evaded or escaped the line-up.

Had I remained in the brigade, I would not have survived any massacre. I was disciplined, punctual, rarely leaving the camp, never shirking from any task or initiative, and I never took sick leave. This made me an easy target, and my survival from any massacre would have been impossible.

What I learned during my visit regarding what transpired within the brigade was that on the morning of January 13, officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers were ordered to assemble in formation under the false pretext of participating in a civilian initiative. The bitter truth was that it was a massive trap, marking the execution of the first phase of the conspiracy within the brigade. An unofficial regional sorting took place during the assembly, followed by their transfer to detention centers. The second phase involved horrific and brutal executions.

This sorting targeted about 85% of the officers, non-commissioned officers, and soldiers from the brigade who hailed from the northern regions—Al-Dhale’e, Yafea, and Radfan—primarily based on their geographical affiliations. This was the first stage of executing the plan within the camp. This is how the brigade was seized. Meanwhile, civilians in various regions were summoned to attend party meetings, leading to arrests and, later, executions. In truth, those who labeled January 13 as a conspiracy were largely correct.

The worst Machiavellian principle was executed here in a grotesque manner: “the end justifies the means.” The ugliness of the conspiracy, the treachery and deceit, and the horror of the execution were all evident. Even more disturbing was that the first criteria for sorting were shockingly and blatantly regional.

Many were executed merely for their geographical affiliations to the north—Al-Dhale’e, Radfan, and Yafea. Some of those I knew well had no interest in politics and had no ties to it, but even this did not save them or alleviate their fate. They were eliminated as part of a bloody and vengeful plan for a resounding defeat.

During my visit to the brigade, I felt deep sorrow, isolation, and profound sadness. I witnessed the stains of blood on the floors and walls of the rooms—remnants of human hair scattered here and there, some still clinging to the walls, with bullet marks standing as stark witnesses to the horror of the act and the criminality of its perpetrator.

Military and civilian clothes stained with blood lay strewn on the ground. The smell of blood and its metallic tang still permeated the air. The corridors whispered of death having passed through, as if death roamed and wreaked havoc everywhere. A sense of desolation inhabited the places and corners. The massacres I encountered were met with retaliatory massacres from the other side, most driven by vengeance, not without regional undertones, leaving the ground saturated with victims.

Lieutenant Alwan, from Ibb Governorate, was in my same company and also my neighbor in Aden. He was a graduate of the military academy’s eleventh batch. He was shot in the waist while attempting to escape an inevitable fate, mere hours away from certain death. He miraculously survived.

In his account, he said:

“They took us from the prison in a packed truck after tying our hands behind our backs. We were all from the north—Yafea, Al-Dhale’e, and Radfan. I felt they wanted to eliminate us, and I rubbed the rope binding my wrists against a protrusion in the truck. It was night, and the darkness was thick.

“On the way, I confirmed that we would be executed in Wadi Hassan. After great effort, I managed to tear my bindings on that protrusion I had been using during the journey. Some of my colleagues, upon realizing their destination and that death was near, began to cry and plead.

“One officer named Nasr, from Radfan, known for his good intentions, after realizing they were heading to Wadi Hassan where death awaited them, asked them to negotiate, trembling with fear. He was like a drowning man trying to grasp at straws, but they mocked him and his plea. Officer Nasr was one of those kind souls indifferent to politics.

“I was the only one who managed to tear my bindings and jump from the truck. They fired at me, hitting me with a bullet in my waist and another in my hand. The darkness was thick, and I kept running while bleeding. They couldn’t catch me, and the darkness aided my escape. I wrapped my wound with my shirt and spent long hours running in the desert, bleeding until I reached the Al-Alam area between Aden and Abyan, where I fainted. I was found by forces from the other side, who rescued me, saving my life.”

There are many tragic accounts. My colleague, First Lieutenant Al-Hayani, a platoon leader in the reconnaissance company, was among others crammed into a cell, numbering more than thirty officers and soldiers. They were subjected to heavy gunfire, and Al-Hayani was shot but did not die. Then, one of them threw a grenade into the room, eliminating those who survived the bullets, ending their lives with an explosion.

* * *