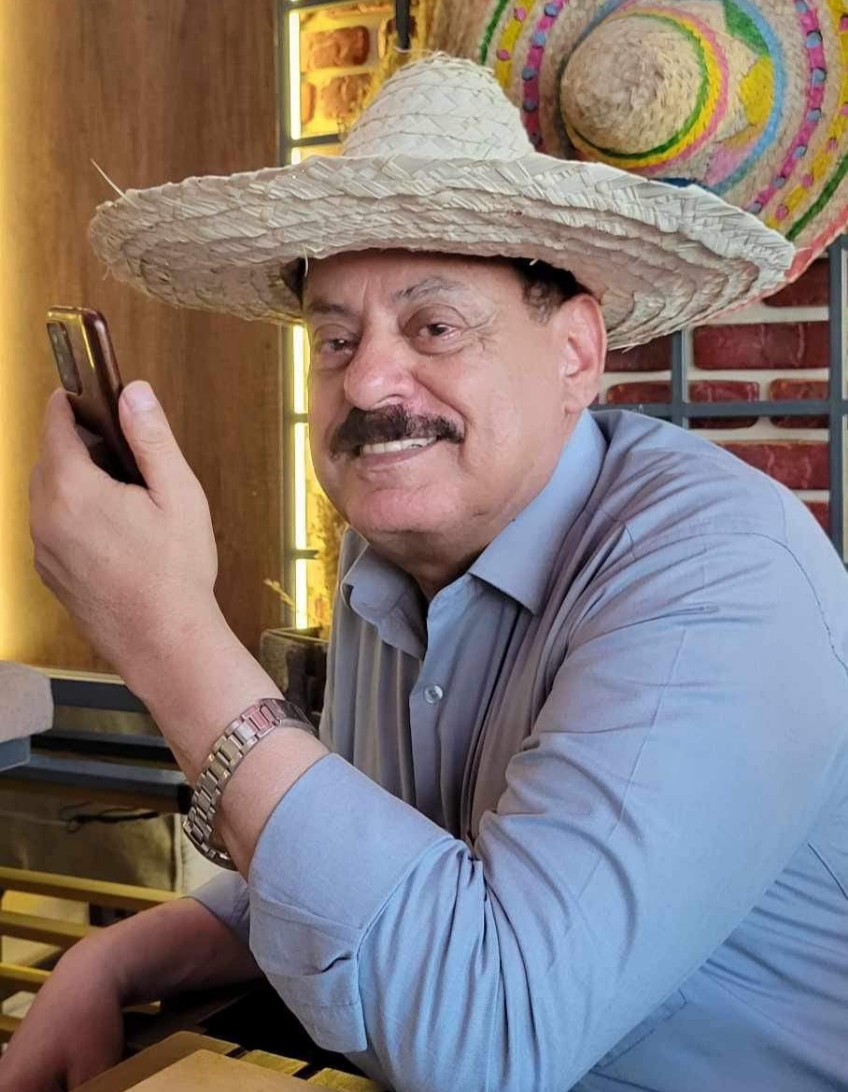

From My Diary in America: The Torment of the Grave in America

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

My friend Al-Harazi, whose name is Abdulwahid Al-Qudaimi from Bani Ismail in Haraz, greets you with a military salute and a face radiant with love. Each time you meet him, you feel a sense of shyness from his warm welcome and heartfelt reception. The features of his face and his cheerful demeanor bring you comfort, tranquility, and peace of mind. He envelops you in familiarity, love, and warmth, seeping into your soul like a stream of fresh water.

His conversation captivates you from the first moment, overflowing with humanity. As you engage in small talk, you feel as if you have known him for ages, showered by a rain of affection. He is a rare human being; it’s hard to find a man like him in reality.

He persistently refused to accept money for the goods I bought from his store. When I began to hesitate in taking what I needed from him, he started accepting a symbolic amount to ease my embarrassment. Yet, I still felt uncomfortable with this arrangement.

My shyness weighed heavily on me, and I found it increasingly difficult to face him. I felt compelled to leave my friend and refrain from buying what I needed without severing the bond of affection and peace between us, promising daily that all was well.

I began to deal with another shopkeeper to avoid my friend Al-Harazi. However, he continued to call me and offer ready meals he prepared at home, not from his store, insisting with oaths of friendship that I accept them. This man overwhelmed me with his generosity, nobility, chivalry, and the grace of his character.

I was confused and often thought about leaving him, departing like a beloved one without a return. But fate had other plans, and I will return to discuss this at another time.

* * *

I dealt with the other shopkeeper, whom I believed to be American of Indian descent or something similar. I didn’t care where he was from as long as he didn’t speak Arabic. I tried to communicate with him using the limited English words I knew, but sometimes I struggled; I relied on gestures at times and handing over items at others.

It was surprising that some English words I had memorized and tried to use were not understood by the shopkeeper. For instance, the word “water” in British English is pronounced differently in American English, and I often had to clarify by gesturing or physically showing him what I meant.

I thought my Arabic tongue was unaccustomed to English, let alone its pronunciation. The truth is, I have difficulty with the pronunciation of Arabic letters as well. My brother Abdulkarim once accused me of mispronouncing certain letters when I read, even swallowing some of them. If this is my situation with Arabic, how would I fare with English? And if American English itself shortens some words and letters from British English, how would someone who struggles with their own language manage with a foreign one? It was undeniably a difficult and complex situation, or so it seemed to me.

* * *

One day, overwhelmed and filled with despair, I carried my medical files and other belongings, feeling burdened by a charlatan and a liar, confronted by a boldness of deceit that sought to crush me. My mind was lost in confusion, searching for an escape from the predicament I was in, while malice tightened its grip around me. There was no honor in this conflict, no knightly duel—just deep pain and a good knight being killed by treachery.

Upon reaching my residence, I searched for my phone but couldn’t find it. I felt as if my memory had become my phone, and I had lost my memory altogether. I asked my roommate if he had my number to call it and check if my phone was in the room. He informed me he didn’t have my number, and regrettably, I hadn’t memorized it. I suggested he call another colleague living with us. When he did, I discovered I had lost my phone, and no one was answering it.

I suspected I might have left it at the building entrance while burdened with my belongings and unlocking the door. I rushed to the entrance but found no trace of it. I hurried to the shop where I had purchased some items, and instead of speaking to the owner in English, I spoke to him in hurried Arabic, feeling panicked and disorganized:

“Did I forget my phone here? Did you find my phone?”

He replied in Arabic, “Where are you from?”

I said, “From Yemen.”

He asked, “Where in Yemen?”

I replied, “From Taiz.”

Then I asked him, “And you, where are you from?”

He answered, “From Rada’a.”

He said, “I thought you were Indian during the time I dealt with you.”

I laughed and said, “I also thought you were Indian.”

We both laughed, and he handed me my phone.

My spirit lifted, and I felt relieved after a period of tightness and stress.

I told myself that a person can turn even their misfortunes into opportunities, as well as into new experiences and acquaintances.

I asked him if I could take a picture with him.

He surprised me by saying sternly, “No, photography is forbidden. Clean your phone of pictures, songs, and videos. Photos and songs are a sin. Do you remember the torment of the grave? Have you heard about what happened to that Egyptian artist in the grave? Clean your phone. Don’t keep any pictures, songs, or videos. Everyone should prepare themselves for departure; death can come at any moment.”

I asked him the name of this Egyptian artist.

He replied that he couldn’t remember but had heard it on YouTube.

I asked him, “Do you believe this?”

He swore an oath, one, two, three times.

I asked him how long he had been here.

He said, “I was born here.”

I left, astonished and alarmed, and never returned.