My Mother Shapes Our Essence

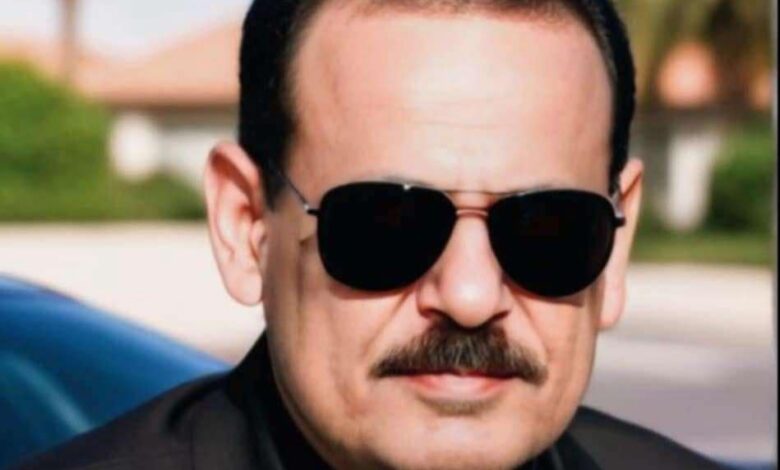

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

My mother is the wellspring of our initial consciousness. She would weave captivating tales for my siblings and me, and we listened, spellbound, hanging on her every word. With each twist and turn in her stories, our eagerness blossomed, longing to know more until she reached the anticipated conclusion.

Our attachment to her storytelling was unwavering, especially as the narratives unfolded into happy endings, where truth triumphed over falsehood and justice prevailed against oppression. We followed the rhythm of her words, holding our breath until we reached the climax, immersing ourselves in the fierce struggle between good and evil.

We gravitated toward goodness, pouring our fervent emotions into her narratives, which concluded in joyful and resplendent victories after a tumultuous back-and-forth of conflict. These tales demanded our attention and appreciation, inviting us to immerse ourselves fully.

Our sensibilities were delicate, our minds pliable, and our awareness sharp and receptive. These stories illuminated goodness, nurturing it within us and compelling us to embrace it. Conversely, they ignited our hatred for injustice, falsehood, and evil, urging us to resist and confront them with unwavering resolve.

Day by day, her tales refined our morals and nurtured our humanity, cultivating our emotions and enhancing our beautiful feelings and sensitive perceptions.

I am a part of you, my mother. To this day, I strive to embody your hopes and wishes — challenging injustice and evil, advocating for goodness, and supporting kindhearted, weary souls. Or so I believe, dear mother.

What my mother shared with us was profoundly wholesome, drawing us in and leaving an indelible impact on our hearts. Her tales resonated deeply, unearthed from the rich tapestry of collective heritage and folk wisdom passed down through generations.

Among the stories she recounted over fifty years ago during our dark and moonlit evenings were: Al-Humaid Ibn Mansour, Abdulrahim, the Pigeon of Maramid, the old soothsayer, “Al-Jarjouf,” the she-wolf, Abu Nuwas, and the Seven Brothers.

I still recall some of the verses of poetry that she would memorize and recite to us. These lines resonated deeply within us, leaving a lasting impression and stirring a profound empathy for the less fortunate. Among those verses are:

The poor man walks, and all stands against him; … Even people shut their doors to him.

The dogs bark when they see him approaching, … Growling and baring their teeth.

Yet, when he passes by, they soften, …Wagging their tails in a show of affection.

In the stories, we listened intently, captivated by her narration, as if she were Buddha and we were her devoted disciples. I often lived the scenes she described, immersing myself in the reality of her tales. I would embody the character of one of the noble heroes, aligning myself with his essence and emotions, responding to his feelings and rhythms. I followed the narrative as one follows the gentle course of a stream, yearning for its conclusion to bring me peace, joy, and tranquil sleep.

Tears would flow silently from my eyes, streaming down my cheeks, some lingering on my lips, where I could feel their warmth and taste their saltiness. I knew my tears as intimately as I knew myself. The night held its own virtue, for it concealed my sorrow from my mother and siblings. My mother’s captivating storytelling style enchanted my siblings, keeping their attention focused and preventing them from prying into my eyes, my tears, and my repressed emotions.

Later in my youth, I was surprised to discover that some of those tales were recorded in the book Yemeni Tales and Legends by Ali Mohammad Abdo. Upon comparison, I found that my mother’s version contained embellishments, perhaps drawn from her imagination or added by the storyteller she had learned from previously.

As for the verses she recited with passion, attributing them to the poor man Abdul Rahim, I knew little about him beyond his identity as a poor poet. It was only as I grew older and read more that I learned those verses were actually attributed to Imam Al-Shafi’ee.

* * *

I can vividly imagine my mother during the first year of my life, striving to teach me the basics of speech. I still see her with a broad, warm smile, encouraging me as she coaxed my tongue to form words. She would repeat simple phrases, her smile radiating encouragement as she taught me the fundamentals of pronunciation: “Allah, Allah… Amma, Amma… Abah, Abah…” I also recall my struggle with speech despite her diligent efforts, perhaps due to some flaw or hindrance in my tongue. It feels as though a barrier exists between me and eloquence; I cannot discern whether this impediment was inherent or developed during a challenging phase of my childhood. What I am certain of is that it has lingered with me to this day.

As I grew, my mother would share stories about God, Muhammad, Ali, and the angels—everything she learned from her ascetic father, who was devoted to reading the Quran. He would narrate tales from the Quran, along with its teachings and interpretations. I was particularly fascinated by the story of Mary and her son Jesus, whose miraculous narrative has stayed with me until now.

As I matured, I began to understand why Christ, in his final moments on the cross, cried out, “My God, why have you forsaken me?” His timeless words, “Let he who is without sin cast the first stone,” moved me deeply. I felt compassion for those who had lost their fathers and empathy for the orphans who bore no guilt. I find myself aligning with victims, regardless of their circumstances, and I comprehend the errors that life inflicts upon humanity.

I learned of the glory and immortality Christ attained after his death or “ascension.” Nietzsche’s saying, “There are people who are born after their death,” resonates with me. Some great individuals achieve recognition only after they have passed away, reborn as giants in the memories of others. They deserve more appreciation than those who attain glory in their lifetimes.

My sorrow deepened when I read that the name of “Christ” was exploited and his blood was used by certain kingdoms and tyrannical empires, along with the scoundrels who ruled them. I learned how nations were oppressed and occupied in his name, and how Christianity became a hell where free thinkers, scholars, and enlightened individuals were cast into the flames.

* * *

My mother often reminded us that God sees us wherever we are and that each of us has two angels: one on our right, recording our good deeds, and another on our left, noting our sins. This idea frequently came to mind during my moments of solitude in the bathroom, whether fulfilling my needs or engaging in masturbation. My mother had warned me against this behavior, telling me that my hand would return swollen with its burden on the Day of Judgment. This notion lingered in my thoughts, a constant presence even into adulthood.

Despite her warnings, I did not heed her advice. Instead, I sank deeper into these habits, perhaps even becoming addicted to them for an extended period. Each time I resolved to quit after indulging, I found myself returning to them with even greater longing and desire than before.

This reflection reminded me of Milan Kundera’s Immortality, where a devout mother encourages her daughter to rid herself of certain habits, saying, “God sees you.” She hoped to steer her daughter away from lying, nail-biting, and nose-picking. Yet, paradoxically, the daughter only envisioned God during those moments of indulgence or shame.

I, too, recalled God whenever I indulged in the actions my mother had warned me against. I engaged in the habit despite this divine oversight, and afterward, I felt an even deeper sense of disappointment and regret. I promised both myself and God that it would be the last time, yet I found myself returning to it, craving it with increasing desire and pleasure.

* * *

My mother frequently warned us with great fervor against the consumption of alcohol, delivering passionate tirades against drinkers, sellers, and anyone associated with it—her anger often exceeding even that of God. This deep-seated hatred, whose origins I cannot pinpoint, remained unknown to her. Little did she realize that her son, fifty years later, would proclaim, “A bunch of drunks doesn’t drown in blood,” in response to the targeting of himself and his companions, as they protested the dire conditions and the bloodshed that had reached unprecedented levels. We came to understand that the life we had hoped would be better had instead become deeply miserable. The heads we had once protected from colds and headaches now seemed worthless, easily lost or shattered by a bullet, potentially fired by someone with little education or culture—or perhaps by those who cannot read or write—while the scoundrels pulled the strings from their safe and fortified perches.

* * *