A Nation of a Billion Golden Souls

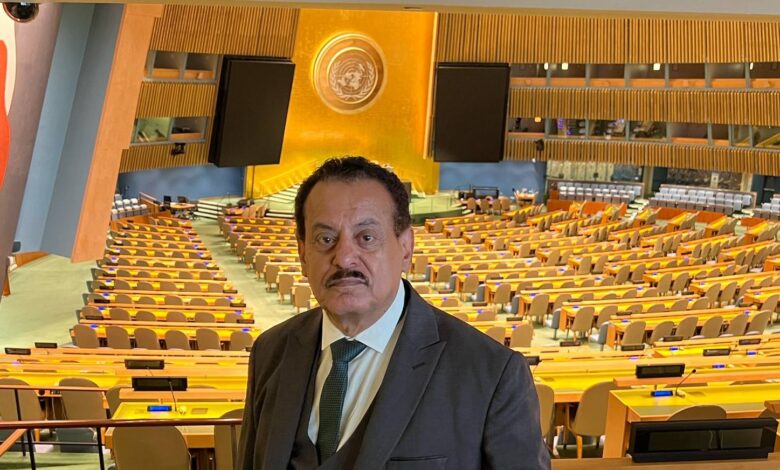

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

Once, I was a sensitive child, overflowing with emotions and feelings. Many of my actions during that vibrant phase of childhood were perhaps natural, driven by the intensity of those feelings. However, some of these have lingered into my adulthood, seeming, to many, unnatural—if not foolish and naïve. What can I do? Within me still resides a child who refuses to grow up and does not wish to die, age, or leave

* * *

I still recall my childhood, when I would place grains of various kinds at the entrances of ant homes for them to feed upon, hoping they would thrive in comfort and ease. I hoped to alleviate their struggles and poverty, to spare them from greater dangers. Sometimes, I would lavish them with generosity, anticipating my delayed return. I never wanted them to stray far from their homes, fearing they might risk their lives under the feet of passersby or the hooves of livestock.

I assisted them in constructing their homes deep in the mud, fortifying them with stones and tin to protect against floods and rain, ensuring their dwellings remained intact, untouched by ruin. This was my way of thinking, and I often attempted to speak to them in solitude, hoping to convey my intentions and warn them of imminent dangers I perceived. I believed ants understood my words as the Prophet Solomon understood the speech of ants.

At times, I would gather stray, lost ants and create a sanctuary for them within an empty tin of powdered milk, filling it with clay to build rooms and storages stocked with grains, so they wouldn’t starve or abandon their newfound homes.

I tended to them for days and weeks. When I traveled to Aden, I took the tin to a remote, safe place, burying it in my father’s land, providing them with ample grains to sustain them for as long as possible, despite my aunt’s protests and her view of me as a deranged child, listening in as I spoke to the ants in my solitude.

* * *

On another occasion, I set a trap for mice. In the morning, I found a mouse lifeless, caught in the grip of the trap, its neck ensnared by iron teeth. Its spirit had departed, perhaps hours earlier.

Beside it lay a small mouse, almost glued to its side in a poignant, sorrowful scene. I watched, feeling its despair paralyze it. I saw it breathing rapidly, burdened by grief, anxiety, and confusion. I expected it to flee at my approach, yet it stood its ground, not attempting to escape.

I tried to awaken his instinct for survival, hoping to stir within him the urge to flee, but he appeared indifferent and unconcerned. He refused to escape, staying close to his mother in that place. I wondered to myself: Is he inexperienced and unaware of the danger threatening him with death and extinction? Or does he only feel comfort in remaining beside his suffocated mother, finding it impossible to leave her, even if that means following her into death?

The scene deeply affected me, and tears streamed from my eyes. I begged forgiveness from the victim who had left this world, though she could no longer grant it, her spirit having ascended to her Creator in the heavens. I tried to atone for my sin by feeding her young one, transferring it to a safe place where it could feed and grow strong, hoping it would live freely. I prayed for its long life and well-being.

I wished to mourn the slain mother, but who would inspire me with a verse or possess me to create a poem? I regretted my actions profoundly, grieving for this fate. I prayed to God for forgiveness, reciting the short verses of the Quran that I had memorized, and I honored her with burial rites that seemed fitting and solemn.

As I grew older, I encountered cunning and treacherous politicians among humankind, who kill the victim and then attend the funeral, gently patting the heads of the victim’s small children, perhaps offering them stipends and gifts. They performed acts of kindness, not out of atonement or guilt, but as a means of deceit, cloaking their true intentions in a guise of compassion, perhaps in search of more victims.

As I delved deeper into life, experience, and history, I read accounts weighed down by tragedies and deep wounds, revealing even stranger realities where the murderer inherits the slain’s wife and wealth, marrying multiple times.

To this day, the question gnaws at my weary head and spirit, echoing in my tired memory: Why does all this happen, and what surpasses it in cruelty during more horrific and brutal wars?

The truth is, it’s more than a question—bigger than confusion, a riddle I have yet to answer, even now that I am over sixty! While the echoes within me wander, asking me, I push them away and suppress them, yet curiosity persists, asking: Why does life give what death takes away? And a whisper of the devil replies: Life cannot be meaningless while death holds wisdom! To avoid slipping into a sea of philosophy and logic, I had to banish both from the entire space.

* * *

I return to the mouse trap, but this time it takes me back to 2005, or perhaps the year that followed, where a similar incident occurred, differing from my childhood experience.

The new event happened in Al “Fakous” building in Sana’a, where I was living. One of my children had set a mouse trap without my knowledge; I caught a mouse by its paw, and oddly enough, several other mice were hovering nearby. Perhaps they were trying to do something beyond their capability, or maybe they didn’t even understand the situation. They seemed to be in pain for their companion, perhaps trying to save it—or at least hoping to in such a harsh moment.

When I witnessed this scene, I rushed to free the mouse caught in the trap. Moreover, I was determined to save all the mice that were circling around it. They deserved to be saved at least because they hadn’t abandoned their companion in its distress; they were the most loyal to it in its plight and suffering.

What struck me even more was the sight of mice lured by food scraps, only to perish in traps driven by the instinct to survive and the urge to eat. Death had become an inescapable threat to them, while their chances of life were dwindling, and their fortunes were scarce, especially as the threats to their existence from humans grew ever larger.

The mice faced difficult choices: if they did not eat, they would die; if they did eat, they would fall victim to a trap or poisonous bait threatening their numbers and survival. Their only fault was the desire to live and reproduce, governed by instincts they were born with. Due to their hunger, they fell into various traps of death, including those specifically targeting their existence.

Driven by their instinct to eat, the mice became victims upon which death feasted. This tragedy finds many parallels among us humans, despite significant differences, though most of them ultimately serve others’ interests.

Many poor people and their children, driven by hunger and need, become the fodder for armies, and through them, blood is shed; wars, fires, and ruins spread. They become the targets and the fuel of these hellish ambitions of those who possess wealth and life, seeking to exploit, subjugate, and enslave, executing acts of ruthless extermination and killing so that the world of the billion can thrive while billions of others perish by a thousand means.

Our fate remains to struggle against this excessive selfishness, to confront this culture steeped in death and its unjust justifications. That saying shall forever resonate in the philosophy of the good in their battle against the wicked: “Even if circumstances prove that ‘the good do not live,’ never seek a vacant place among the wicked.”

* * *