From My Diary in America .. My Friend Al Harazi

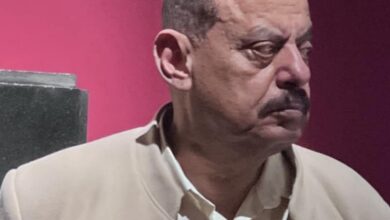

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

Hunger suddenly descended upon my body, ambushing me like a predator lying in wait. My legs felt weak, on the verge of collapsing under my own weight. I was dripping with sweat, my hands trembling, losing control of their steadiness. My entire body seemed ready to crumble into a heap of debris.

There was no restaurant nearby. My feet could no longer carry me to the nearest eatery, which felt distant and out of reach. I stumbled into a nearby grocery store, my steps unsteady, as if I were trying to explore something in a hurry.

I approached a foreign worker in the store who was stuffing pastries with various fillings, names of which I couldn’t recall in English, and some I didn’t even know in Arabic. I attempted to communicate with him, but we were lost in translation.

* * *

I tried to find a translation app, hoping it might rescue me from my predicament. My trembling hands felt uncooperative, and my mind seemed to fade away. I felt lost, unable to concentrate, struggling to piece together my scattered thoughts, filled with confusion and uncertainty.

With what little strength I had left, I tried to withdraw, dragging my weary steps toward the door when suddenly, the store owner called out to me, asking, “Where are you from?”

My face lit up when I heard him speaking Arabic, and I replied, “I’m Yemeni.”

I then asked, “And where are you from?

He answered, “From Haraz.”

In that moment, I felt a door of joy open and envelop me with warmth.

* * *

I ate a piece of chocolate and felt a wave of refreshment and balance wash over me, as if I had narrowly escaped a crisis. My health was improving. We started chatting, and I sensed he recognized me, but that didn’t stop me from asking:

Do you know me from before?

He replied, “No.”

Then I asked, “Do you know Majed Zayed?”

He answered, “No.”

I realized that this man had been away for a long time. I then asked, “Do you know Abdu Bashr?”

He said, “Yes, but only a limited acquaintance. We had a few brief meetings a long time ago,” without hiding his admiration for the man, emphasizing it with the word “Tahtouh” which means “a shrewd man”.

I felt an unusual warmth and familiarity from his kindness towards me, as if I had known him for a long time. His face was friendly, his love abundant, and his kindness overwhelming. He asked the worker in English to prepare something more than what I wanted, with generous hospitality.

* * *

When I asked Al Harazi about the cost of what I had taken, he refused and insisted he wouldn’t take a single cent. I thought this would be a one-time occurrence, something that sometimes happens here, especially if you’re a Yemeni newcomer to America.

In the area where I live, which some call “Little Yemen,” there are over fifty thousand Yemenis. There are some grocery stores, restaurants, and retail shops owned by Yemenis; even their names are in Arabic on the signs. There is also a street named after Ibrahim Al-Hamdi, and you can find some Yemeni products in larger grocery stores, like Shamlan water and Abu Wald biscuits.

On the second day, the same scene repeated itself, with added details. When I asked him about the amount, he swore again that I wouldn’t pay a single cent. I introduced myself as a member of the Yemeni Parliament to convey that I was capable, even though the reality was quite the opposite. Yet, I felt he understood my nature better than I did.

He persistently urged me to have coffee, water, or any drink with the sandwich pastry, while I refused with a painful pride, claiming that I had everything I needed.

With the repetition and the embarrassment overwhelming me, I felt as if I were standing naked before him. Since he had memorized my situation and traits, he too felt shy and made sure not to hurt my feelings. More than once, I sensed he was even more embarrassed than I was, but it was difficult for me to interrupt him because I felt an unusual warmth towards him.

I told him, “You know me well. You know my details without even telling me.” He would respond that he didn’t know anything about me and had never heard my name before. The man was successful in sinking me deeper into my confusion.

I said, “Please, I want to be your customer. If you continue like this, you’ll cut me off, and I won’t see you again, which saddens me. This happened to me with a generous grocery owner down the street, and I had to leave him, and I don’t want that to happen here again.”

However, Al Harazi immediately raised his hand, warning me that if he saw me in the street, he wouldn’t say “peace be upon you.” To soften the situation, he would sell to me at half price or even more sometimes, justifying it with “my capital without loss.”

I felt he did this to ease my spirit and lessen the weight of my embarrassment. I accepted this arrangement and became his customer, starting to eat two meals a day instead of one—one from him and another from a nearby restaurant.

I found myself exhausted by my shyness, grappling with the challenge I faced, and burdened by a miserable situation. Meanwhile, a petty official in Sana’a accused me of being a secret agent, and an inflated figure in the “legitimacy” mocked me without knowing the hardships I was enduring and the existential struggle I faced between compounded illness, financial strain, and the relentless misery of filthy pens digging their rusty blades into my weary body.

* * *