Shepherding the Sheep

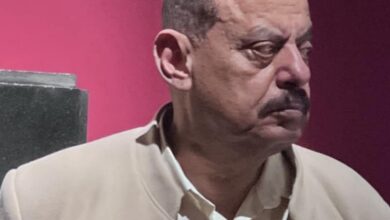

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

My younger sister, Nadia, shared the task of shepherding the sheep with me. She would often deliberately defy me, ignoring my calls and rebelling against my authority, treating me as if I were an old man burdened by age and senility.

I would strike her repeatedly and with severity, sometimes leaving me feeling exhausted. Unfortunately, I repeated this behavior once with my son, Fadi—a regret I still harbor deep within me. I remember it with great sorrow, filling my heart with grief and remorse.

Thus, violence recurs, and cruelty in interactions is passed down from father to son, and from son to those beneath him.

This dynamic is mirrored in the authority of a president over his subordinates, a manager over his employees. This situation is not limited to individuals in society; it extends to nations and what is referred to as the international community.

The relationships between nations often center on the subjugation of weaker states by more powerful ones. The weaker nations compensate for their vulnerabilities by exerting dominance over their own people, intensifying oppression, humiliation, and subjugation.

They persist in coercing and subjugating their citizens through every available means of repression, wielding the power and influence they possess, particularly the resources of the people they oppress.

* * *

Our flock of sheep was small at first, but it grew in number, never reaching a large size. I herded the sheep during my youth, still a child exploring the thresholds of life with my tender fingers. I have many stories and deep connections with the sheep.

The sheep belonging to my parents filled my small world with memories that have proven resistant to fading over the more than fifty years that have passed. No sunset or forgetfulness has erased them.

My memories of the sheep I tended are still vivid in my heart and mind, despite more than half a century of a rich, tumultuous life filled with everything imaginable. The memories and images I hold dear have not faded, even if they have drifted far from me or if I have soared high to the moon.

I still remember the names of those sheep, their shapes, and many of their stories, while I find my memory struggles to recall my son’s age!

My memory is still ablaze with details from over fifty years ago, while other more recent memories elude me, some of which are hardly a stone’s throw away.

The same memory that retained those details betrays me when it comes to what is more important and more recent.

* * *

In 2009, when a Swiss immigration judge asked me during the interview about my children’s names and ages, I was flustered by a question that should have had an obvious answer. I failed to mention the names of my seven children.

I struggled even more to identify the age of any of them, leaving the judge astonished, who compared us to a farm of rabbits as I resorted to the trick of arranging them with a year’s difference between each one.

Meanwhile, the Palestinian translator scrutinized my face, pointing out that I resembled President Saleh—though I had never seen anyone among us who shared that resemblance. But I realized that we Yemenis also seem similar to outsiders, just like Koreans, Chinese, and others.

In conclusion, it is beautiful and important to retain memories of all that is lovely and nostalgic, but without forgetting what is more significant.

* * *

In wonder, there is also bitterness and tragedy. Our collective memory today, in some respects, lives in a state of deep-seated hatred, recalling a distant history soaked in blood, reviving the burdens of enmity and grievances from the wide-ranging tragedies that occurred fourteen hundred years ago and continue to this day.

Our history is filled with massacres, bloodshed, hatred, and the most painful and bitter reality is that we do not seek to learn from what has happened as a lesson or a moral. Instead, we exert tremendous effort to entrench and foolishly repeat it, or we re-produce it in a multiplied manner, dragging it along with all its tyranny, oppression, savagery, and horror, in an attempt to impose it on a future that we neither can nor will be able to overcome its challenges.

How we long today to transcend this rubble that weighs as heavily as mountains. We need to strive toward the future, to rise and confront its challenges; without this, we will continue to live in death, blood, and hatred until extinction.

I wouldn’t say it’s certain that we can escape the misery, backwardness, and dissolution we find ourselves in.

* * *

I still remember “Hajb” and “Khors,” as well as “Biraq,” and the rebellion of “Enab,” which fits the saying “wherever it is tethered, it finds its place.” I remember “Qadriyah” and “Bahriyah,” my poor mother’s sheep. These were some of the elements of my small world that I once lived in and belonged to.

I still recall “Hajb,” the milking goat, whose body was larger than usual, said to be descended from an ancient Indian lineage. When my father called her from the mountaintop, she would come rushing to him.

One day, she was afflicted by the “evil eye” and died—at least that’s what they claimed!

I remember the goat “Khors,” from whom my mother gave me her unborn kid as a reward for my care of the family’s sheep and for my diligent efforts in herding them. I named the unborn kid “Biraq” before her mother gave birth, and she was the first possession I could call my own.

The blind poet Bashar Ibn Burd begins one of his poems with: “O people, my ear is in love with some of the living… and the ear sometimes loves before the eye.” I fell in love with “Biraq” even before I had seen her or heard her voice, and even before her mother gave birth to her. It was a captivating and enchanting love from a child who yearned for his dream to have a presence that could accommodate both him and his great affection.

I loved “Biraq” while she was still in her mother’s womb, growing and developing gradually. I watched her mother’s swelling belly every day, like a farmer awaiting the harvest, or a child eager for the dawn of Eid, hastening its arrival to rejoice, don new clothes, and unleash joy into the air.

“Biraq” emerged from her mother’s belly into the world, radiant as the fresh morning. Beautiful as the deep, dark eye with its black and white. Her birth enveloped me in a joy so immense that it could not be contained within the universe itself.

“Biraq,” the hornless goat, grew up peacefully. She does not love wars; neither does she care for youthfulness or military displays. Gentle as a dove, her whiteness as pure as snow. When she is sad, her sorrow is as dark as mourning attire.

I continued to raise her, surrounding her with care, tending to her day by day. I earned her through my persistent efforts and nourished her with the sweat of my brow. There was no suspicion of ownership by another, no corruption tainting her, and no piety under the influence of evil. Each day, “Biraq” grew, but she did not rush through any stage, nor did she regress to the age of dinosaurs. She did not reach out to a killer, nor did she steal from a suffering people, nor did she take the rights of the needy and the poor.

Perhaps “Biraq” does not pray or flatter, but she possesses a purity that could nourish a land and its people with clean water. She grows as God intended, without the oppression of our days and months, nor does she rely on poisons and drugs to hasten her growth. She develops slowly, not at the speed of corruption seen in the petty states and militias ruled by warlords.

She speaks plainly without slander or pretense, without turning the back of a grasshopper into the feathers of a dove or silk, and she does not create art from the croaking of frogs.

* * *