The Stigma Impeding Knowledge

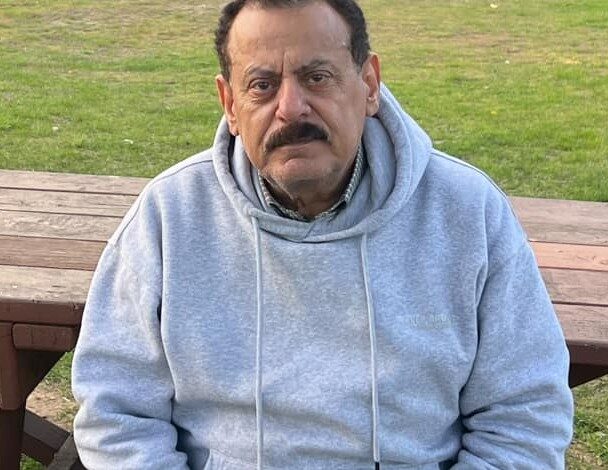

Yemeni mp

Ahmed Saif Hashed

I often found myself wondering, instinctively driven by a knowledge that still cradles my existence. I attempted to explore the beginnings of my world. Some things that seemed obvious were still shrouded in mystery, confusion, and questions. With the innocence of a child, I would ask my mother, leaping from the tangible to the abstract, from the concrete to the metaphysical. These were questions posed by a child still new to his world.

At times, I sought to understand my immediate surroundings through inquiry. Other times, I ventured into existential and grander matters. A question might appear simple in one context yet daunting in another. It could go unanswered, or the response could be misleading due to social constraints, ignorance, or other reasons that I struggled to understand.

I was unaware of certain limitations imposed by societal taboos. I couldn’t distinguish between permissible and forbidden questions, nor did I realize that some areas were off-limits for inquiry.

Occasionally, I would unknowingly rebel against the usual norms, knocking on the door of the unspeakable and traversing the forbidden in a reality burdened by the weight of the past, the stigma of shame, and the oppressive power of fear. There was often public reprimand awaiting those who transgressed boundaries, even if they were innocent children trying to explore their world.

Questions, when answered, often led to further inquiries, generating a cascade of thoughts.

Some answers, no matter how erroneous or willfully deceitful, would initially convince me of their validity. Eventually, those questions would resurface, reignited by doubt, revelation, or new developments.

In later stages of my understanding, I would find that my earlier beliefs had faded, and my satisfaction had waned. I grew skeptical of previous answers, with doubt overshadowing the question itself, causing it to reemerge with greater intensity and urgency.

Sometimes my mother would resort to clever lies in response to my inquiries, avoiding the obligation to answer my questions. This was perhaps due to a heavy social stigma from her perspective. Often, these fibs were short-lived, echoing the saying, “A lie has a short lifespan.” When situations changed, that question would resurface, demanding an answer, especially as the previous response grew weak or unconvincing.

* * *

I would ask my mother questions without realizing that she would have to lie to answer them, due to shame and its implications. I would inquire about my existence: how I emerged from her womb into this world and from where exactly I came. When my mother gave birth and I saw my newborn sibling, I would repeat the same question insistently, dismissing her previous explanation as it had lost its credibility.

Initially, my mother would laugh or smile, claiming we emerged from her knee. After some time or with another birth, I would find myself asking again, having seen the newborn was larger than her knee, and seeing no evidence of the alleged birth from that knee. The question regained its prominence as I realized my mother’s earlier answer was either obscured or false, or simply no longer convincing.

I would hear my mother’s moans of agony during childbirth, but they would prevent me from entering the room, forcibly moving me away. This separation was often mixed with the hope of some attending women attempting to shield me from hearing her suffering. I was told only that my mother was in labor, with an update to follow—whether I had a brother or sister.

I was not allowed to enter until everything had concluded. Upon entering, I would see the cord hanging from the ceiling and smell the incense, myrrh, and other birthing essentials burning, which my mother consumed to alleviate the pain. Yet, these things could not reveal or answer my question: how and from where did my sibling emerge?

The question would insistently reappear, as my mother’s previous answer seemed decayed or overtaken by blatant doubt. She would try to convince me again that we were born from her navel, which deepened my skepticism.

I wondered how a navel, with an opening no larger than a fingertip, could accommodate a newborn larger than both her knee and navel combined.

Then my mother would unleash her third lie, claiming that my siblings and I emerged from her mouth. But how could any mouth, no matter how wide, expel a larger being? Why hadn’t she choked? How could a larger newborn exit from a mouth smaller than itself?

Sometimes, my mother would ignore my questions, or laugh at them when others were present. Her responses, often accompanied by a smile, would magnify my doubts both then and later.

Eventually, I learned the truth, though not as early as some children today grasp concepts we once overlooked. I discovered that we waste years of knowledge due to the stigma that hinders our eager minds from soaring. I recognized that shame delays many truths that should have become fundamental knowledge in childhood. It became crucial to do whatever we can to liberate ourselves from this burden that weighs heavily upon us, especially when it transforms into an obstacle to learning and understanding.

In a comparative context, my mother’s responses in those days seem trivial compared to what we experience today. Her incorrect or deceitful answers were motivated by a desire to shield me from shame, preserving modesty and decorum of the time. In contrast, the lies from those who govern us today stem from self-preservation, betrayal, corruption, and the committing of horrific crimes against the citizenry and homeland.

* * *

In school, I also encountered shame as an additional obstacle to knowledge. I vividly recall an incident that remains etched in my memory.

While my science teacher was engrossed in explaining a lesson, I listened intently, yet the term “feces” recurred in his explanation without me knowing what it meant! I could not grasp the lesson due to my ignorance of the term, especially since it was the first time I had heard it. I felt certain my classmates were in the same boat, though perhaps they lacked the courage to ask. I raised my hand and asked the teacher, “What is feces?”

He responded with annoyance, gesturing irritably, attempting to make me feel foolish, providing a one-word answer: “Excrement.” Laughter erupted in the classroom, leaving me deeply embarrassed. Had he asked my classmates, they would have faltered in their responses as well. I bore the brunt of the embarrassment alone, while everyone else benefited from his answer, and that day I was the martyr of the lesson.

This term resurfaced for me fifty years later when a leader of an authority in Sana’a responded to my protest and defense of our people with the phrase, “All excrement.” The contrast between my noble teacher, who was embarrassed to answer out of modesty, and what this president said highlights the unfortunate depths and farce we have reached—a reality we live today with pain and bitterness. Here, shame has its purpose and necessity.

* * *